Q&A with Author Peter Bowling Anderson

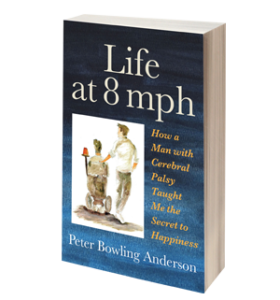

Peter Bowling Anderson has a master’s degree in communications/writing from Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, an M.A. in teaching from Centenary College, and a special education certification from LSU Shreveport. His writing has appeared in a variety of publications, but perhaps his most important work experience came as a tutor and assistant for Richard Herrin, a man with cerebral palsy who unexpectedly became Peter’s friend, mentor, teacher, and inspiration. Life at 8 mph: How a Man with Cerebral Palsy Taught Me the Secret to Happiness is Peter’s account of an extraordinary friendship and the joys that can be found by saying yes to the unknown.

What prompted you to write your memoir and share your personal experiences with readers?

What prompted you to write your memoir and share your personal experiences with readers?

It was an idea I’d toyed with for several years since my time ended with Richard. I thought our time together would make a good inspirational tale, but I was involved in other projects. Then I got married, and then we had our son, Henry, so it kept getting pushed to the back burner. … An opportunity finally arose in 2017 to tackle it, and though it had been five years since we’d worked together, I was lucky enough to have the support and endless patience of Richard and his wife, Della, who answered all of my many, many questions to fill in the gaps and sweep away the cobwebs as I wrote the book. I knew Richard and I had experienced enough hilarious and poignant moments that it would make an entertaining tale if I could just get it down on paper, and thankfully, I finally did.

Which writers and works inspired you to put your own story on paper? Who has influenced your writing style?

My favorite authors are Richard Ford and Cormac McCarthy. They both write literary fiction about the “blue-collar” world. Ford’s stories are primarily set in the North, McCarthy’s in the South. Their writing is profoundly insightful, the type of prose I can reread several times and still learn new things. They mix in humor, too, which I think is important and I try to do. Annie Dillard, Norman Maclean, and Richard Russo are three other authors I love, as well as Anne Tyler. I like authors with a good ear for dialogue, a great sense of humor, and a keen sense of why people react the way they do in certain situations. Richard Ford once said in an interview that he wasn’t interested in the crisis but in how people reacted to the crisis, because that was the most informative aspect. I agree. I hope my book makes people think about how they might react, or have reacted in the past, in certain situations with someone with a physical challenge, and what they can glean from it.

What makes a great memoir? What advice would you give to other aspiring authors who might be struggling to get started with a memoir?

Two things I’ve noticed in effective memoirs are transparency and pace. In Edward Abbey’s Desert Solitaire, or Annie Dillard’s Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, or Norman Maclean’s A River Runs Through It, they all keep the story moving. There’s no indulgent, laborious fixation on a particular passage of time. These authors all understood that, while their stories were fascinating in different ways, they were still their stories, and to keep readers intrigued, they needed to keep the action moving forward. Everyone has a story to tell, but if you want anyone to listen to the whole thing, you better keep it moving. I tried to do that, as well as to be transparent and not hold anything back, as these authors did. I believe the reader can tell when a writer is being authentic and unguarded or writing merely to impress. Candor seems to be the most memorable approach.

What challenges did you face in creating memorable scenes that seamlessly brought together multiple storylines?

What challenges did you face in creating memorable scenes that seamlessly brought together multiple storylines?

I’d written another memoir a few years earlier about the ten dogs we had in our home while I was growing up. There were lots of humorous stories, but one thing I noticed when it was finished was that it tended to feel a bit too anecdotal, with just one story followed by another unrelated story. The only common thread was that all the stories concerned the dogs. So with this memoir, I wanted the story to have a definitive narrative arc, which, thankfully, it did naturally all on its own. When I took the job working with Richard, it was the last job I wanted and I thought I’d hate it. Later, I began warming up to him and to the job, and by the end of the book it turned out to be the best position I ever had. This memoir goes from Point A to Point B to Point C, rather than being just a series of stories. I think having that arc helps it flow more smoothly and keeps all of our experiences connected.

Your writing style is both earnest and humorous. How did you strike that balance?

Lots of practice, and years of bad writing. I began writing at nineteen, and my first attempts tended to err on the mawkish side. I wanted so desperately to move people that I went overboard and made it melodramatic. It took me a while to rein it in, and in particular, to learn the valuable lesson that it’s much easier to touch people if I’ve already made them laugh. When a writer can make the reader laugh, it establishes a bond, or acceptance, that then allows poignancy a much easier path. I think of it as a relationship between two friends—if they’ve already bonded over good times, they’ll be more likely to lower their emotional guards when it’s time for serious discussions.

What has been the most fulfilling part of the writing and publishing process for you?

On the writing end, it was extremely fulfilling to finally get Richard’s story down on paper. I’d told him years ago that I would one day write a book about our time together, so the guilt had weighed on me rather heavily as the years passed. Plus, I thought people would benefit from reading the story, so I wanted to get it done. … To have Richard’s story finally cross the ultimate finish line to be published so the public can read it is as satisfying as anything I’ve ever accomplished.

What’s the primary takeaway you hope readers get from Life at 8 mph?

I want readers to remember that people with injuries, illnesses, physical challenges, etc., still have many valuable things to offer. Just because they’re restricted in some way doesn’t mean they’re incapable of blessing our lives. In fact, their unique situation often offers them a specific perspective that allows them insight we simply don’t, or can’t, see. It behooves us to take the time to listen to what they have to say. Also, I hope readers pay attention to the fact that working with Richard was the last thing I wanted to do, yet it turned out to be the best job I ever had. Way too often, we decide what will work for us or be beneficial for us before we’ve even given it a try, and we end up missing out on so many wonderful experiences that would allow us to grow in immeasurable ways. In fact, as I look back at my life, almost every time I was certain I didn’t want to do something because I wouldn’t like it but then I finally did it anyway, it wound up being the perfect choice and I was fortunate and grateful I took a chance. Opportunities don’t always come packaged the way we’d envisioned, but we need to open them anyway, like all gifts, before tossing them out. There might be fine diamonds stuffed in those socks.