Author Post: My Scars Are My Veins of Gold

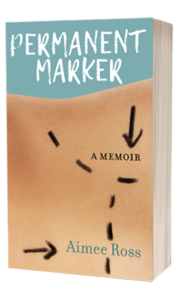

Aimee Ross is a nationally award-winning educator who has been a high school English teacher for the past twenty-five years and who published Permanent Marker: A Memoir in 2018. She completed her MFA in Creative Non-Fiction Writing at Ashland University in 2014, and her writing has been published on lifein10minutes.com and SixHens.com, as well as in Beauty around the World: A Cultural Encyclopedia, Scars: An Anthology, Today I Made a Difference: A Collection of Inspirational Stories from America’s Top Educators, and Teaching Tolerance magazine.

Aimee Ross is a nationally award-winning educator who has been a high school English teacher for the past twenty-five years and who published Permanent Marker: A Memoir in 2018. She completed her MFA in Creative Non-Fiction Writing at Ashland University in 2014, and her writing has been published on lifein10minutes.com and SixHens.com, as well as in Beauty around the World: A Cultural Encyclopedia, Scars: An Anthology, Today I Made a Difference: A Collection of Inspirational Stories from America’s Top Educators, and Teaching Tolerance magazine.

My Scars Are My Veins of Gold

Scars: marks left on the skin or within body tissue where fibrous connective tissue develops to connect, support, and bind as a wound heals. Scars can fade, be covered up or even be surgically altered, but they can never go away.

They remember.

Scar Tissue

I can count more than ten scars all over my body from that night.

(The ones I can see, I mean.)

Some are short, some are long, and some are ugly. The back of my left arm looks like Dr. Frankenstein stitched it together, my foot has permanent weird lumps and a raised center that makes wearing shoes difficult, and my belly, well, I hated the monstrous, gaping scar that ran its length. Doctors had to put me back together—literally. They told me so.

Strangely, most of the scars are also vertical.

At right angles to a horizontal plane. Perpendicular.

The same angle at which we collided when he ran that stop sign and into my car, T-boning it and me. We were on our way home from dance camp that July evening. The three girls in my car escaped the wreck with minor injuries—thankfully. I barely survived. He died.

Four months later, a highway patrolman visited to share the other driver’s toxicology report and to inform me of my rights as a “victim of a crime.” He came to bring me “some peace of mind.”

It didn’t work.

A young man of only nineteen years got into a car with two different drugs in his body. He caused a tragic wreck and lost his life. He forever changed mine. (Cause for the scars I can’t see.)

And all of my scars, both physical and emotional, tell a story of survival, one in which I found out how truly resilient the human body and spirit can be.

Kintsugi as Metaphor

One day in my classroom, Kaitlyn, a senior a month from graduation, told me to look up Japanese art called “kint”-something. I was amazed.

Kintsugi: a Japanese word that means “golden joinery.” It originated in the fifteenth century when a Japanese shogun broke his favorite bowl and tried to have it repaired by sending it back to China. Metal staples were used, which displeased the shogun, so he hired Japanese craftsmen to find a better answer. Their solution? Reparation of the breakage with seams of gold—kintsugi. Thus, the piece became more valuable than before it broke.

Kintsugi: a Japanese word that means “golden joinery.” It originated in the fifteenth century when a Japanese shogun broke his favorite bowl and tried to have it repaired by sending it back to China. Metal staples were used, which displeased the shogun, so he hired Japanese craftsmen to find a better answer. Their solution? Reparation of the breakage with seams of gold—kintsugi. Thus, the piece became more valuable than before it broke.

More beautiful. An art form.

Maybe it was time to embrace my scars. And maybe my breakage could become a part of my history, making me more valuable, rather than causing embarrassment or avoidance or erasure from memory. Maybe, like that broken bowl, I could be better than new. Perhaps an even more beautiful version of who I’d been.

I liked that.

Illumination

It’s been eight years since the accident—enough time to no longer be defined by the experience, though it will forever mark me. Enough time to not notice my scars anymore. They are simply a part of my body’s canvas now, a part of who I am. I might even be proud of them.

“We had to have them do that,” my brother once said, pointing to my abdomen, where the worst, most noticeable scar was, “to be able to have you here now.”

That.

At the time, a way inside. A way to save my life.

My scars—the physical and the emotional—are marks of resilience and endurance. They demonstrate a strength of spirit and a willingness to fight that I never knew I had. I survived. I did it.

And not only am I stronger because of them, someone loves me in spite of them.

My new, loving husband, Jackson, didn’t know me before the accident. He accepted and embraced my flaws, and it’s meant all the difference. This new, fuller life of love and energy post-accident shows in my very being. So many people still tell me how happy I look and that I “glow,” especially around Jackson.

But I think it’s just the veins of gold running through me.

Aimee Ross was living a perfectly normal life raising three kids, married to her high school sweetheart, and teaching at her high school alma mater. Life was perfect—right until it wasn’t.

Aimee Ross was living a perfectly normal life raising three kids, married to her high school sweetheart, and teaching at her high school alma mater. Life was perfect—right until it wasn’t. Which writers and works inspired you to put your own story on paper? Who has influenced your writing style?

Which writers and works inspired you to put your own story on paper? Who has influenced your writing style?