Q&A with Author Barbara Moran

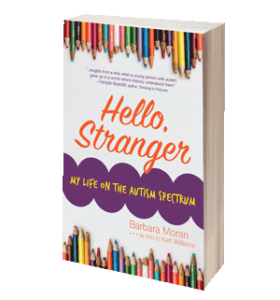

Barbara Moran is a graphic artist from Topeka, Kansas, who was not diagnosed with autism until she was in her early forties. She has spoken at autism conferences, and her artwork has been exhibited by Visionaries + Voices, at Bryn Mawr’s annual Art Ability show, and at the MIND Institute at the University of California-Davis. Barbara’s art often focuses on personified objects such as locomotives, stoplights, and cathedrals. Barbara shares her home with her companion of forty years, Rooney, a 1934 Monitor Top GE refrigerator. Her memoir, Hello, Stranger: My Life on the Autism Spectrum, will be published in March 2019.

What inspired you to work with Karl Williams and share your story with the world?

What inspired you to work with Karl Williams and share your story with the world?

I always wanted to write my life story but lacked the skills or patience to do it. When I met Karl, he gave me the opportunity to write a story. Without Karl’s help, there’d be no story. Karl offered to do the interviews and make a story out of them. And working with those original transcripts must have been like trying to unscramble an egg.

What do you want readers to understand about you after they’ve read Hello, Stranger?

I want to be validated. And I’d like to hear from people who have had similar struggles with sensory issues: I want to hear someone say, “Me, too.” I spent most of my life without knowing anyone with sensory issues and I felt a lot of shame because of people’s expectations of me—which I learned were unrealistic. No one even knew that sensory issues existed, and that caused people to want me to just stop complaining. It was my sensory issues that made me withdraw in the first place. And so I personified objects because they wouldn’t overwhelm me like people often did.

I want to be validated. And I’d like to hear from people who have had similar struggles with sensory issues: I want to hear someone say, “Me, too.” I spent most of my life without knowing anyone with sensory issues and I felt a lot of shame because of people’s expectations of me—which I learned were unrealistic. No one even knew that sensory issues existed, and that caused people to want me to just stop complaining. It was my sensory issues that made me withdraw in the first place. And so I personified objects because they wouldn’t overwhelm me like people often did.

What do you hope readers learn about autism and people with autism?

I want them to imagine what autism can be like, to understand the emotions that drive a lot of autistic behavior. Autistic people can be hard to live with, but the autistic person does want help. It needs to start with feeling better; anything that helps sensory processing can help behavior. And relationship-based social skills training, which is give-and-take, can help the autistic person in being able to be functional. A person shouldn’t have to squash her personality to merely be tolerated. The more welcome she can feel with people, the more she’ll care. People need to communicate clearly basic social rules and limits, but the autistic person needs to have enough flexibility so they aren’t constantly afraid of being in trouble.

How did your life change after you first were diagnosed with autism in your forties?

Having an autism diagnosis answered my question finally: Why was my life so out of synch with everyone else’s?

At Menninger’s, I was told that people choose to be mentally ill. After that I felt shame—like it was my fault. I felt shame most of my life. Being diagnosed with autism was like being forgiven. My problems weren’t character faults; they were legitimate complaints. It was like the Ugly Duckling learning he was a swan. At conferences, I was treated like a poster child—a celebrity—and people lined up to buy my pictures. It was amazing to me that someone from Kansas would get to attend so many conferences and feel welcome.

As you look back on your life, how has your view of your childhood experiences evolved?

My view of my childhood changed for the better because knowing “why” meant I no longer needed to blame anyone or accept blame myself. My parents hadn’t harmed me; my problem was physical.

How has drawing helped you throughout your life?

I have always liked colorful pictures regardless of who produced them. And I’ve always enjoyed producing images myself. My drawing has allowed me to see what I wanted to see.

How do you perceive your autism today? Do you see it primarily as a challenge? Can it be interpreted as a gift in some way?

Autism can bring gifts to some people like Temple Grandin: She has a LIFE. But unless something changes drastically, autism has few real advantages. I’m better off than most. Only a handful of autistic people live on their own and are able to work. Something needs to be done to help those with autism become more functional so they can tolerate life. Being autistic is often painful and lonely. I don’t think medication is the answer. There needs to be more emphasis on nutrition and relationships and sensory integration, which has been proven to work—and the person needs a say in the treatment plan.

Autistic people need to communicate and be listened to even if what they say sounds like crazy talk. If somebody knows she counts, other people’s wishes will matter more to her.